‘Hostile Terrain 94’

Toe-Tag Exhibit at UCSB Portrays Crossing Deaths in ‘Hostile Terrain 94’

by Charles Donelan | Published January 30, 2020

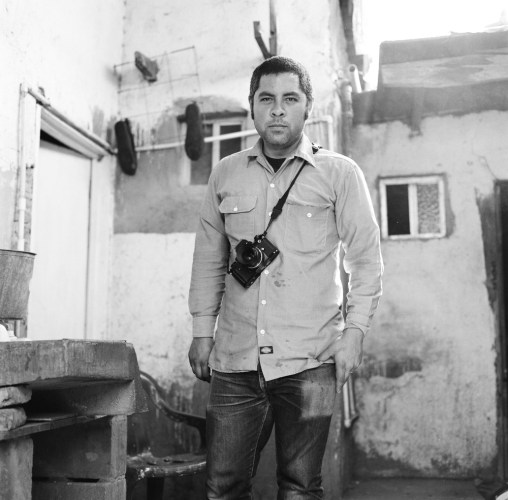

Photos by Michael Wells

In a gallery at the back of UCSB’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum, four folding worktables face a large map dotted with location markers and hung with clusters of yellow and orange tags. More tags sit in stacks on each of the tables, along with manila envelopes and pages of printouts from a database.

Opposite the map, on the two walls that flank the entrance to the room, dozens of stained and tattered T-shirts form a haphazard collage. On one side of the space, there’s a shelf displaying similarly distressed items, things like torn canvas shoes and a waterlogged diary; on the other, there’s a video monitor displaying drone footage of the Sonoran Desert in Arizona. The exhibition is called Hostile Terrain 94, and it is one of more than 150 such stations set up around the world this year by a team led by UCLA professor of anthropology and 2017 MacArthur Award recipient Jason De León.

In order to fully appreciate Hostile Terrain 94, you need to follow the exhibit’s instructions. I’ve spent some part of the last two Saturdays participating in the show. Seated at one of the worktables in front of the map, I used black pen to fill out the slips of cardboard and string known as “toe tags,” which morgues use to identify dead bodies. From the printed spreadsheets, I dutifully copied the 14 data fields onto each tag I made by hand, writing down case numbers and location information. Some of the categories — state, county, and latitude and longitude — were familiar. Others, such as “surface management” and “corridor” were new to me. The work was at once relatively easy and impossibly difficult.

The heart of the process comes through most strongly in the five fields labeled name, age, cause of death, OME determined COD, and body condition. For example, “Armando Delgado Gil, 33, exposure, probable hypothermia, fully fleshed.” There are two types of toe tag — manila, for corpses that have been identified, like that of Armando; and orange, for the large number of cases in which the identity of the body remains unknown. The causes of death and body condition fields on these orange tags offer such details as “skeletal remains,” “complete skeletonization with bone degradation,” and “skeletonization, disarticulated.” Whether the tags are manila or orange, the bodies they describe all have one thing in common: They perished in the process of crossing the border from Mexico into the United States.

Pushed to Death

As a result of a U.S. border-enforcement policy introduced in the 1990s called Prevention Through Deterrence, or PTD, thousands of corpses have accumulated in the most remote and dangerous areas along the border between the United States and Mexico. By focusing enforcement personnel and infrastructure in urban areas, the United States government has deliberately forced border crossers to take their chances in increasingly treacherous terrain. Enlisting the extremes of weather found in these places, along with such natural predators as rattlesnakes, scorpions, and coyotes, the Border Patrol has weaponized the desert, turning nature into something much more deadly than any moat or wall.

The more than 3,200 people who have lost their lives in this way, and whose deaths are documented by Hostile Terrain 94, are victims of deadly force just as surely as the young men of color who have been gunned down in the streets of Chicago and St. Louis, and no bullets were fired. PTD may claim to deter people from crossing the border illegally, but writing toe tags has given me a different view on those three letters. An interpretation that takes into account the results of this policy might yield something more like “Pushed to Death.”

Jason De León did not start out as an activist. His work at the border began when he discovered that the field and lab skills he had acquired on archaeological digs for ancient Meso-American artifacts had suddenly become relevant in the killing fields of the Sonoran Desert, where human remains were piling up at an alarming rate. De León documented this state of affairs in a book, The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail (2015), but when Donald Trump was elected in 2016, he put off another book project in favor of doing something more public. What 2016 did, he told me, was intensify his search for a way to “convey social science data through things that people can connect with.” “We are in an important election cycle,” he went on to say, “and I felt that I had to make a choice: Either I could hide away and finish a book that wouldn’t come out for another year and a half, or I could try to do something more public facing that would raise awareness,” not just about what was happening in Sonora but about the plight of migrants worldwide.

De León is no stranger to the public eye. In 2011, he cohosted a Discovery Channel series with another professor of anthropology, Kirk French, called American Treasure. The pair traveled around the country answering requests from people who believed they had stumbled on important historical artifacts. It was a kind of younger, edgier Antiques Roadshow shot on location, rather than in a studio.

In 2012, De León created the Undocumented Migration Project while on faculty at the University of Michigan, and in the years that followed, he took graduate students and the photographer Michael Wells to the Sonoran Desert, where they excavated and classified not only human remains but also the vast detritus scattered along el camino, the wilderness trail to America. This research, along with Wells’s photos, went into the book, and the detritus — T-shirts, backpacks, water bottles, sneakers, etc. — went into an exhibition called State of Exception/Estado de Excepción, that traveled around the country and received positive notice form the New York Times when it landed at the gallery of the Parsons School of Art in 2017.

His next attempt to bring his border research to the gallery space resulted in a powerful show in Portland, Maine, but the big map of the desert in that exhibit was a static representation covered with red dots marking the locations where bodies were found. Determined to bring the reality of these deaths closer to his audience, De León asked a group of students he was teaching at Franklin & Marshall College in 2018 to start writing toe tags. It took five of them almost three months to copy over the project’s 3,200, and by the end, they were exhausted. Their remarks about how emotionally draining the work had been led De León to a breakthrough. What if the exhibition were designed to draw visitors into this work? What if the conversion of spreadsheet entries to handwritten tags could be crowdsourced? How would that affect the experience of people encountering the show?

For De León, State of Exception and the subsequent show in Portland forced a breakthrough and a turning point. State of Exception’s extensive media component, which included floor projections and other high-tech elements, made it prohibitively expensive. Only a few museums could afford to display it. When it came time to try again with Hostile Terrain, De León knew he wanted to make something that would be affordable for even the most humble spaces. As a result, Hostile Terrain is available for approximately $1,500 to any organization willing and able to host it. In some locations, where its relevance is urgent and resources are slim, even that small fee has been waived.

More Than Four Fields

In order to understand both the exhibition and the scientific project of which it is a part, it’s necessary to look at how many different aspects of the discipline of anthropology are engaged by this work. Anthropologists ordinarily stick to one of the subject’s four fields — physical anthropology, which studies human remains in order to understand the impact of environment and culture on human evolution; cultural anthropology, sometimes known as ethnology, which studies the learned aspects of human communities; linguistic anthropology; and archeology, which examines the objects that people have made. In relation to these divisions within the discipline, Hostile Terrain 94 is a scientific unicorn — a so-called “four-field project” that combines all the different branches of anthropology into a single overarching structure of knowledge. For example, De León’s chapters in The Land of Open Graves on the role language plays in the communities formed by crossing the border are among his most exciting.

Yet even this description, despite the degree to which it reflects an extraordinary synthesis within the discipline of anthropology, fails to cover the scope of Hostile Terrain’s intellectual and cultural footprint. From an art historical point of view, the show reflects a significant step beyond participatory art into the realm of a movement that has come to be called “relational aesthetics.” Interactive art asked visitors to touch the sculpture or play games with a computer interface. In relational aesthetics, the aims are more ambitious. Works belonging to this category take as their point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space. This is one of the main reasons why De León wants to keep Hostile Terrain cheap or free — to allow it to spread throughout the world and take on different configurations in each location.

Finally, contemporary philosophy supplies many of the threshold concepts De León and his colleagues in public anthropology are now using to understand such extreme situations at the weaponization of nature. In this respect, the project extends work done by Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben into the domain of hard data. Agamben in particular — with his theory of the way states of exception, such as the extra-legal status of undocumented immigrants, reduce human beings to “bare life,” a sheerly biological existence stripped of human rights — has become a leader in this regard. Other threshold concepts used in the work include the “hybrid collectif,” a neologism of cultural anthropology that describes the way multiple forces, such as predators, climate, and terrain, come together to cause death in the desert.

Former acting director of the UCSB Art, Design & Architecture Museum Elyse Gonzales made the decision to bring the exhibition to Santa Barbara based on a recommendation from UCSB Assistant Professor of Art History and Archeology Alicia Boswell. Silvia Perea, current acting director of the AD&A, makes several excellent points in contextualizing the work. First, one should understand that the subject is hardly a new one for art. Perea traces the emergence of “Border Art” to at least the 1980s and names multiple other practitioners such as Sislej Xhafa, Kimsooja, Tony Capellán, Hew Locke, and Alfredo Jaar. Second, and perhaps more importantly, she reminds us of the degree to which De León has sought in this project to avoid the aura of “trauma voyeurism” that clings to such recent accounts of Mexican migration as the popular novel American Dirt. All the objects in the show — the shirts, the shoes, the toothbrushes, the water bottles, and the saint cards — are part of an archaeological archive that De León has created at UCLA. The cataloging and archiving of these remains was done in close consultation with the families of the people to which the items belonged.

There’s a quote at the head of chapter four of The Land of Open Graves from the French cultural theorist Roland Barthes that reads, “I lend myself to the social game. I pose, I know I am posing, I want you to know that I am posing, but … this additional message must in no way alter the precious essence of my individuality: what I am apart from any effigy.” De León uses it to set up a moving description of the role that ribald, self-deprecating humor plays in the emotional survival strategies of the crossers. In pondering the depth of this project, and in attempting to respond to the “whole of human relations” aspect of participating in it, I am drawn to an aphorism from Franz Kafka, someone for whom the paradoxes of such states of exception were a fundamental premise of existence. Kafka writes, “You can withdraw from the sufferings of the world — that possibility is open to you and accords with your nature — but perhaps that withdrawal is the only suffering you might be able to avoid.” Thanks to Hostile Terrain 94, we may be able to follow Kafka in seeking to avoid the suffering of withdrawal from suffering just a little longer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.