Botanist Sherwin Carlquist believed keeping plants indoors was a form of torturing the plants because they were not outdoors in a natural environment. In 1956, when he was 26, he designed his and his parents’ Hope Ranch home, blending Japanese and mid-century-modern design on a large lot with a view of the Channel Islands. Less than a decade later, he had authored his first milestone book on the biology of islands and began replacing the Hope Ranch lawn with botanic specimens from distant islands and continents.

Sherwin made dozens of trips to islands all over the world. In October 1966, he spent a week marooned on a small atoll — the Pearl and Hermes Reef — 1,300 miles northwest of Honolulu. The Coast Guard cadets who had rowed him to a sandbar to study its plants couldn’t relocate the tiny islet for several days when they returned to fetch him, its loftiest point being almost invisible at only eight feet above sea level.

Sherwin was stranded among some of his favorite research subjects — native plants of the Hawaiian island chain, the world’s most remote archipelago.

His island research dated to 1953, first on a Scripps Institute field trip to the Revillagigedo Islands southwest of Cabo San Lucas, and then in July when his mother, author Helen Bauer, gave him a cash 23rd birthday gift, which he used for a trip to Hawai‘i.

Bauer had by that time accepted her son’s passion for botany and may have regretted her scolding him when, as a teenager, he “squandered money” by purchasing research papers published by the California Academy of Sciences.

In 1966, he was awarded the Fellows Medal by that same Academy, and by the time of his death in December 2021, Sherwin himself had authored more than 300 published research papers and eight noted books on botanical science.

That 1953 trip to Hawai‘i was Sherwin’s first extensive fieldwork, work that lasted a lifetime. He hiked alone, a beginning graduate student in botany at UC Berkeley, later reminiscing, “I didn’t have a lot of confidence in myself.” His instinctive curiosity and aptitude for observation of plants and their environment had the perfect outdoor workshop as he hiked down into the Haleakala Crater on Maui and noticed the resinous scent of the iconic, charismatic silverswords, in full bloom, growing where few plants can on that harsh volcanic mountaintop.

He recognized the silverswords’ scent as similar to that of the tarweeds he’d studied and collected along the highway between his home in Southern California and the Berkeley campus. After further study, he concluded the Hawaiian silverswords are relatives of the California tarweeds and must have arrived in Hawai‘i via long-distance dispersal.

A relative of the Hawaiian silverswords, the rare endemic California plant genus Carlquista (Muir’s tarplant) was named in Sherwin’s honor in 1999. In 2003, 50 years after his olfactory discovery on Maui, he wrote about these plants in his edited book Tarweeds and Silverswords.

Sherwin’s 1953 fieldwork was the beginning of his studies of how plants got to islands and how they changed after they arrived. He considered islands the “laboratories of evolution.” Sherwin was controversial in concluding that many island species arrived on birds or by sea, and not on land bridges or as islands rafted away from continents. His research led to three important books: Island Life (1965), Hawaii: A Natural History (1970), and Island Biology (1974). In Island Life, he showed how long-distance dispersal could account for the entire native Hawaiian flora.

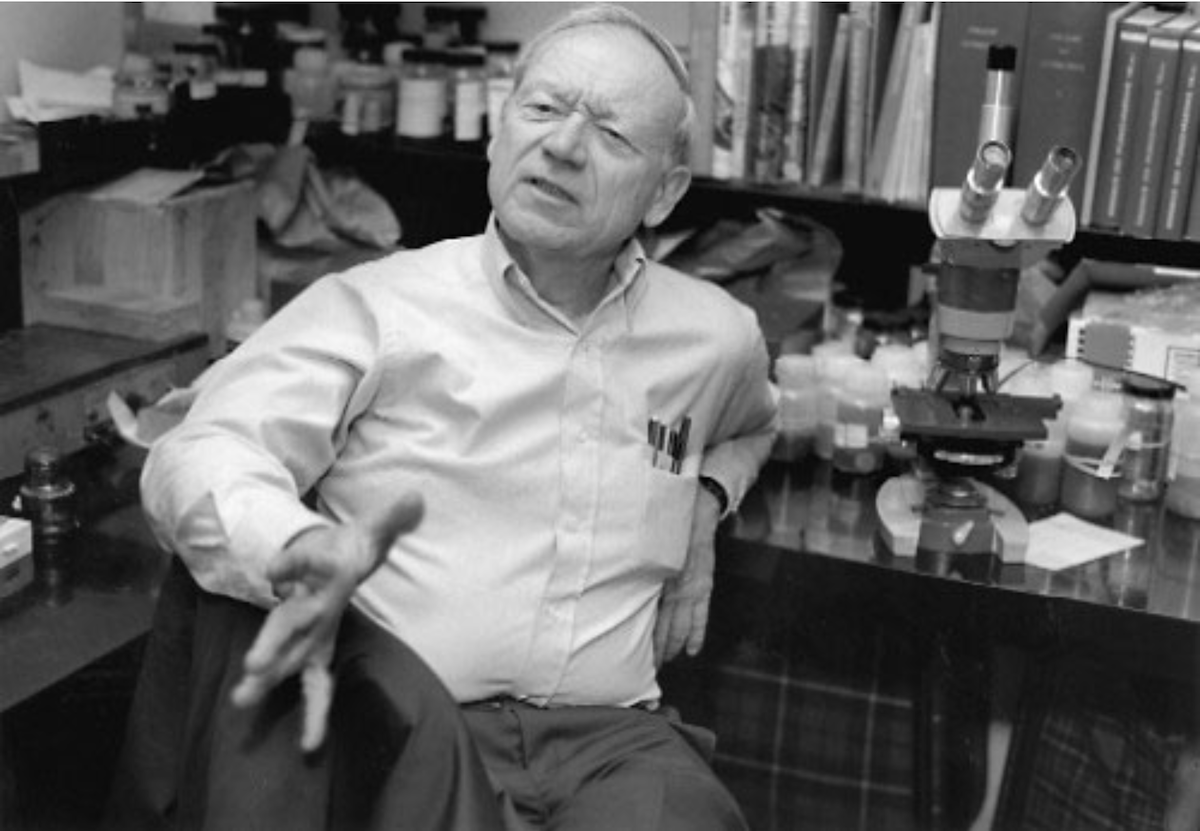

From the 1950s on, one of Sherwin’s main research interests was wood anatomy. In 1966, he revolutionized the field of wood anatomy with a paper describing that wood is a key aspect of the ways that plants adapt to different climates and evolve different shapes and sizes. In 1988, he published the most comprehensive book in the field, Comparative Wood Anatomy, now entering its third edition.

While doing field work in Western Australia in 1974, Sherwin discovered many new plant species, including a new genus, Alexgeorgea, on the remote plain of white sand near Jurien Bay. It was the world’s first known wind-pollinated plant with underground female flowers.

Sherwin loved sports cars and photography. One of his students, Gary Wallace, recently recalled remote desert collecting trips with Sherwin in his tiny Porsche 914. Over several decades, he took hundreds of thousands of plant photographs using his favorite Hasselblad camera. In darkrooms, he developed and printed all of his own black-and-white photos. As an impoverished post-doctoral student at Harvard, he spent the 1955 Christmas holiday sleeping on plant press blotters on the Herbarium darkroom floor, undetected by security guards. He once threw out all of his packed clothes as he returned from Australia so he could bring back 40 pounds of exposed film from his field work in his airplane luggage.

Sherwin’s passions for photography, the outdoors, and the male human form merged in his publication of 10 books — the Natural Man series — of his photographs of natural men in the natural environment. Many of the photographs were taken in the unusual garden at his Hope Ranch home, as well as Joshua Tree, Big Sur, and the Sierra. He was honored when the Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York City produced a one-man exhibition of his Natural Man photographs in 2009, which he was very proud to attend in person.

Sherwin Carlquist was born in Los Angeles in 1930 and grew up admiring the living botanical collections at the nearby Huntington Library. After his studies at Berkeley and Harvard, he spent 37 years on the faculty of the Claremont colleges and Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden.

While living in Los Angeles, he developed a long friendship with Dr. Evelyn Hooker, a UCLA psychologist and seminal researcher, whose studies for the National Institute of Mental Health recommended the decriminalization of homosexuality and the American Psychiatric Association’s decision to remove homosexuality from its handbook of disorders in 1973. Sherwin met many of Dr. Hooker’s friends, including Christopher Isherwood and his partner, Don Bachardy, and with her enjoyed a large circle of friends in the then-primarily underground Los Angeles gay community, as well as the Mattachine Society, one of the earliest gay rights organizations, established in Los Angeles in the early 1950s.

Sherwin returned to Santa Barbara full time upon his retirement in 1993. He moved his research to the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, where he intensified his work with the scanning electron microscope, which gave insight unavailable on the light microscope, and worked as adjunct faculty at UCSB.

After spending 30 years developing his unique multi-continental botanic garden on Via Huerto in Hope Ranch, he could spend more time enjoying the birds and other fauna that visited the Echiums from the Canary Islands; Schotia, an African legume; Puya, a South American bromeliad; Ficus petiolaris, a Mexican white-barked fig tree; and a wonderful sticky-fruited Pisonia from Hawai‘i.

Sherwin also found time to volunteer as a receptionist at the Pacific Pride Foundation and Cottage Hospital. Gay youth seeking therapy services and hospital visitors would likely not have known that the soft-spoken gentleman at the front desk had completed botanical field work from New Zealand’s subantarctic islands to southern Africa and South America; mounted daring helicopter expeditions to northern Australia’s remote Arnhem Land plateau, funded by National Geographic; scaled New Caledonia’s highest peak; and was once marooned on a remote Hawaiian atoll — nor that he had received awards from the Smithsonian Institution, the Linnean Society of London, and the Botanical Society of America, as well as been named a John Simon Guggenheim Fellow.

Instead, they would have met a man who asked how he could help them.

In 2012, at age 82, Sherwin wrote a colleague, “If I have a legacy to leave, it’s inspiring people to go further and do their own things.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.