Eight years ago, on November 22, county movers and shakers — armed with ceremonial ribbon-cutting scissors — opened the county’s brand-new Crisis Stabilization Unit, a 23-hour mental-health treatment center with eight recliners and staffed by clinicians trained to treat people on the verge of a mental-health precipice. There were lots of balloons and optimistic speeches delivered that day.

The CSU, as it was called, would offer a place for people who would otherwise find themselves in the county’s perpetually overwhelmed Psychiatric Health Facility (PHF) — with its scant 16 beds — or sent to facilities out of the county. In the first three months of that year, the county had exported 1,111 people in acute psychiatric distress to such places.

“This is the most exciting day for the county,” exclaimed then-supervisor Janet Wolf. The CSU would lighten the load on the county’s PHF, reserved for patients determined to pose an imminent threat to themselves or others and placed on involuntary holds. At the CSU, people in crisis could voluntarily decompress and then obtain longer-term treatment closer to home.

Fast-forward to the present.

The CSU, administered by the county’s Behavioral Health Department, remains very much a dream unrealized, operating at less than half of its licensed capacity. Since May 2022, it’s been shut down completely. Plans to reopen the CSU — reengineered to function as a locked facility now able to accept patients placed on involuntary, as well as voluntary, holds — have been thwarted yet again.

Mental-health administrators say they’ll have a better idea in August when the new reopening date might be. Chronic staffing shortages — especially for high-end skilled clinical positions — has so plagued the Department of Behavioral Wellness that administrators are now authorized to pay $90,000 signing bonuses to recruit new psychiatrists. For the time being, however, it’s all hands on deck to keep the county’s critically needed PHF staffed at levels required to continue operating as a 16-bed facility. Accordingly, all CSU staff has been transferred to the PHF.

This underscores the extent to which the 16 beds at the PHF have been nowhere near enough to meet the demand. So limited is that PHF bed space that Santa Barbara County is the only county in all of California where law enforcement officers do not issue 5150 involuntary mental-health holds on individuals deemed a threat to themselves or others.

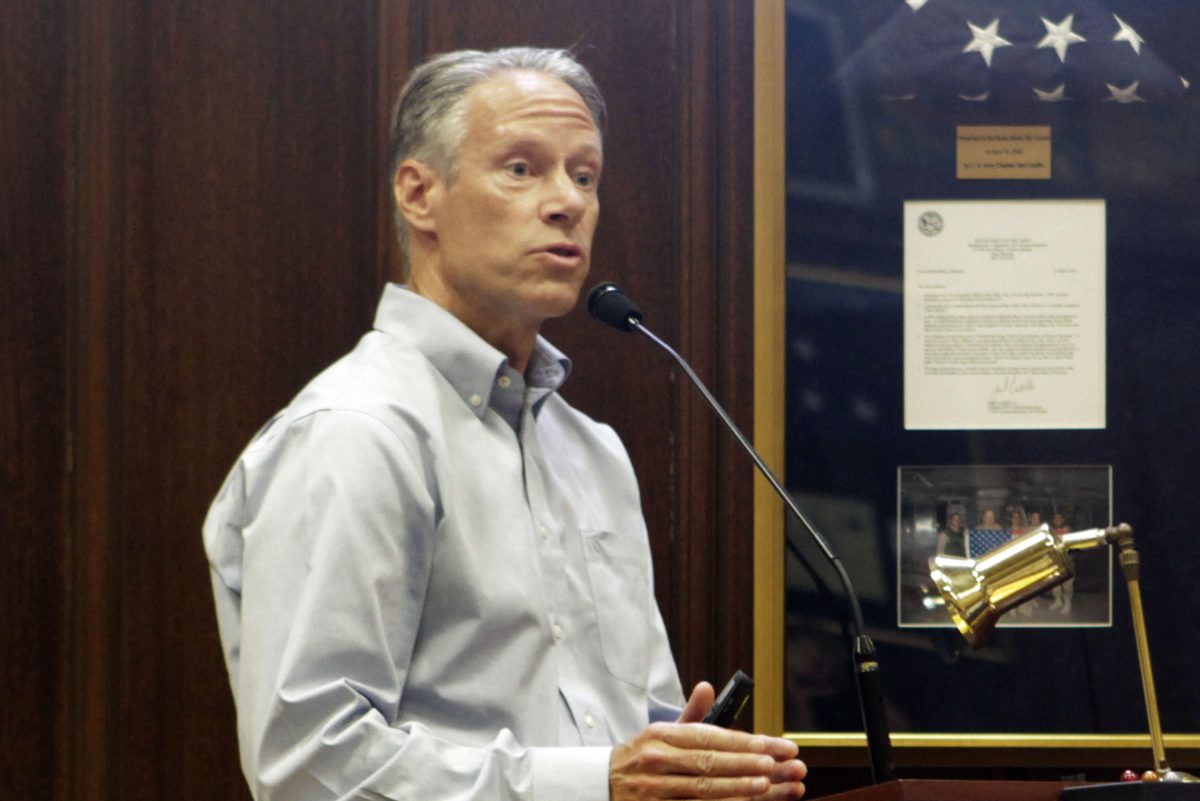

The utility of — and need for — a locked CSU was highlighted at a downtown forum hosted last Thursday evening by mental-health advocates associated with the local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Dr. David Ketelaar, the emergency room medical director and consultant for Marian Medical Center in Santa Maria, described the arduous journey he undertook to get such a facility licensed and built and the results since it opened last September. Ketelaar, who’s been with Marian since 1997, said their Outpatient Psychiatric Unit (OPU) has now treated nearly 500 patients experiencing “very significant crisis.” The impact on the hospital’s emergency room, he said was immediate: Prior to OPU, the average acute mental-health patient would spend more than 30 hours in the ER awaiting treatment. Since OPU opened, that time had plummeted with 70 percent released to their own homes.

Cottage Hospital’s director of psychiatry, Paul Erickson, expressed some astonishment at Ketelaar’s numbers, noting that Cottage releases only 30-40 percent of its 5150 emergency room admissions back home. (Cottage has created a special emergency room holding unit to handle patients experiencing acute mental-health crises; it sees about 70-80 such patients a month.)

In response, Ketelaar explained that many patients are so hard to place with follow-up inpatient care that they’ll remain in the OPU for several days. During that time, Ketelaar noted, the acuity of the crisis will subside to a point where some patients no longer require inpatient treatment and can safely be referred back home. But he bemoaned the lack of follow-up options available to mental-health patients.

For patients needing follow-up treatment for heart problems — or other traditional medical trauma — the referral time would be one or two hours; for those with mental health problems, a four-to-six-hour wait is often required, and not infrequently considerably more than that. That should not be the case, he said, in an integrated trauma care system.

Making matters tougher still, Ketelaar explained, is that most of the patients seen at the OPU are Medi-Cal recipients for whom reimbursement rates are notably lower than what’s provided by private insurers. “This is not an easy undertaking,” he said. When he initially broached the issue of opening a locked facility on Marian’s medical campus, he said all the experts told him he should pursue a voluntary holding model instead.

The voluntary approach is much cheaper, he said, and the licensing requirements far less stringent. But he pushed for the involuntary approach anyway. “This is one part of the continuum. It’s not a fix-all,” he said. “But it’s where the patients are.” He said the facility cost Marian more than $2 million to build and that the state oversight agencies made the task significantly more difficult. “We’re in Santa Barbara County. That makes us both small enough and big enough to make a difference when we advocate with one voice.”

Marian’s OPU is not open to walk-in patients or drop-offs by law enforcement. Given the acuity of some patients — who share a common open space — that could pose security and safety concerns. All patients must be screened by the emergency department first. Ketelaar said he hopes the OPU will get more use as other physicians — especially the county’s psychiatric practitioners — can make referrals as well.

Ketelaar got the biggest applause of the night when he took decisive issue with the county’s often-stated strategy on providing more outpatient care options in hopes of reducing the need for inpatient beds, such as at the PHF. “I’ve been hearing that concept for three decades now and it hasn’t worked,” Ketelaar stated. “Can we stop that conversation?”

In a follow up e-mail, Ketelaar elaborated, “For three decades, all the improvements in outpatient care have NOT gotten us to a steady state where we have adequate inpatient bed capacity.”

Grand juries for just as long have highlighted the county’s acute shortage of acute care beds. Even with 16 beds, they’ve concluded the PHF is woefully small to serve the county’s needs. But many of the 16 beds — as many as half — are often filled by individuals not experiencing an acute crisis but who have been deemed by the court as being incompetent to stand trial. Mental-health advocates have long been advocating for more beds and some county supervisors are now pushing Behavioral Wellness administrators to provide them an assessment of just how many more beds they think Santa Barbara County needs. That number does not currently exist. The supervisors are scheduled to hear that matter mid-July.

on Google

on Google