Channel Island Shipwrecks Tell Stories of Heroism, Heartbreak, and High-Seas Scalawaggery

Our Ocean Bottom Is Rich with History, but There’s Still Much More to Be Discovered

By Tyler Hayden | Published February 27, 2020

Over the last two centuries, some 300 ships have met their fate among the rocks and reefs of the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Stately four-masted steamships ferrying gold and lumber, nimble rumrunners dodging the Coast Guard, rustbucket harpooners hunting seal and otter — all done in by the tricky currents and erratic weather that churn through the crossing. Fog has always been the real killer, especially in the days before GPS. It can come on fast and thick, frightening even the saltiest of captains and forcing them to navigate blindly. The curved west side of San Miguel Island is known as the “catcher’s mitt” because of it.

Among the scores of wrecks out there, historians have identified just 25. The rest are either lost forever or just waiting to be discovered. But finding them isn’t easy. Their remains are often camouflaged under marine growth. “You really gotta take a loooong look,” explained Robert Schwemmer, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration diver and archeologist known as the Indiana Jones of West Coast shipwrecks. He uses old photos and newspaper clippings to get a general idea of where a boat might be before organizing an expedition. “You try to identify manmade shapes, like straight lines and symmetrical curves. Most people can swim right over them and not see them.”

Those that do are treated to rare glimpses into our historic maritime past — visible relics such as boilers, paddle-wheel shafts, and engine blocks, as well as smaller treasures. Schwemmer remembers finding a French perfume bottle in the wreck of the Winfield Scott, which went down off Anacapa Island in 1853. “What’s the story behind that?” he asked. “Did it belong to a man bringing it back for his wife? Did he trade for it in San Francisco? That’s what I love about this.”

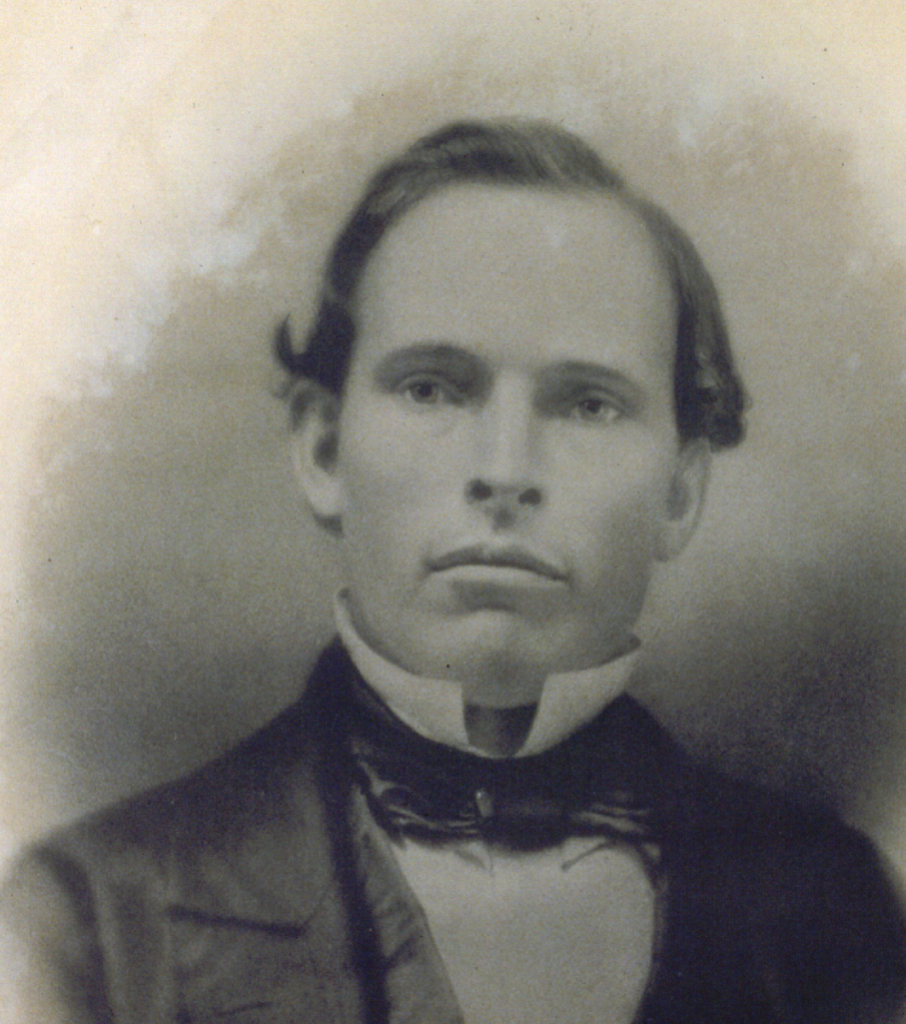

Then there is the thrill when his discoveries reach people whose ancestors had been affected by the shipwrecks. Just recently, Santa Maria resident Dr. Jens Frederik Jarlshoi Birkholm got in touch after hearing that the George E. Billings was found near Santa Barbara Island. Birkholm’s grandfather Frederik S. Birkholm had captained the Billings, and he had the pictures to prove it. He’d always hoped the ship would turn up and complete that chapter of his family’s history. “These discoveries bring to life important human stories,” Schwemmer said.

As excited as Schwemmer gets about these discoveries, he gets just as serious when talking about the regulations that protect them. The wrecks sit in the jurisdiction of the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, which means they’re closely guarded by federal antiquity laws. Without the proper permit, it’s illegal to remove or damage the wrecks or the artifacts among them. “Fines are steep, up to six figures,” he warned. “And if you’re doing something commercially, it could mean the loss of your boat.”

If you come across a new wreck site, officials ask, note its location, take a picture, and report it to the sanctuary at (805) 966-7107.

Scientists like Schwemmer are more interested in facts than legends, but some are just too enticing to ignore. One has it that a gold-filled Manila galleon — one of the famed Spanish trading ships that sailed from the Philippines to California and then to Acapulco from the 16th through the 19th centuries — might be down there. Their route went right along the islands, and around a dozen of them disappeared somewhere in the Pacific. The supposed discovery of a golden captain’s ring off San Miguel in 1974 piqued a lot of interest, but historians remained dubious.

Still, it seems reasonable to assume that one of the Chumash tomols or a Chinese “junk” that used to catch abalone and smuggle opium during the late 1800s might be waiting to be discovered beneath the sea. This year, Schwemmer plans to investigate three “targets” off Anacapa Island using an ROV, or remotely operated vehicle. “They look like shipwrecks, but we’ll see,” he said.

And Schwemmer hasn’t given up on the Watson A. West, a 192-foot schooner swallowed by the sea in 1923. Her crew of nine escaped on a skiff before she sank. They rowed for 18 hours to reach Santa Barbara, where they arrived “exhausted, hungry, thirsty, and half-clad,” news reports said. The Watson is somewhere off San Miguel, and she remains the largest vessel in the area yet to be found. “I still would love to locate that,” Schwemmer said.

Acknowledgment: Much of the information and many of the photographs in this story were sourced from Islapedia.com, a comprehensive database covering hundreds of topics and thousands of entries on all eight California Channel Islands. It was started in 1973 by cultural anthropologist Marla Daily, president of the Santa Cruz Island Foundation, and is a continuing research work in process.

1. Comet

The Comet was a three-masted lumber schooner built in 1886 by the Hall Brothers of Washington State, who designed some of the finest and fastest sailing ships of the era. She was carrying 620,000 feet of redwood lumber when, at 11 p.m. on August 30, 1911, she lost her way in a pea-soup fog and ran into Wilson Rock off San Miguel Island. The captain blamed the collision on a faulty chronometer, a timekeeping device used to determine longitude, which put the vessel eight miles off its course. A 24-year-old German crew member, Hans Mailborn, was killed in the incident and his body lost at sea.

Captain Henry H. Short of Santa Barbara purchased the Comet’s salvage rights. He rafted most of the lumber to South Coast lumberyards and sold the rest to the Vail & Vickers Company on San Miguel Island, which used it in the construction of new ranch buildings.

The following January, Japanese fishermen found “the body of a white man on the extreme end of San Miguel,” a Los Angeles Times article states. “While not identified, it is supposed to have been that of the mate of the lumber schooner Comet, wrecked off San Miguel last fall…. The Japanese dug a grave and buried the man, marking the place. Captain Short verified the story by going to see the freshly formed mound.” The next month, Short’s right hand and leg were crushed aboard the Comet as he continued salvage operations, but he recovered at Cottage Hospital.

2. Aggi

“Lashed by mad seas and hammered against the rocks of Talcott Reef, the Norwegian ship Aggi Norge went to pieces this morning.” That was the 1915 news report describing the last moments of the Aggi at the west end of Santa Rosa Island. She was headed to Sweden, laden with 600 tons of beans and 2,500 tons of barley. All 20 of her crew survived, though the first mate, Hans Thormadsen, “became insane in Chicago on his way home to Norway,” according to the Santa Barbara Morning Press. “This is attributed to his severe experiences while this ship was battered by the storm.”

Two weeks later, the Universal Film Company purchased the wreck with intentions of using it as an underwater set. Santa Barbara sailor Scott Cunningham, however, expressed doubt that the Aggi’s broken remains would stand up to the continuing bad weather. “They’ll have to hurry up with their moving pictures,” Cunningham told the Morning Press. “The wreck will soon be only a dream — and you can’t photograph a dream.” He turned out to be right, as the sea soon knocked the Aggi into even smaller scraps useless for filming.

In 1967, a dive boat operator named Glenn Miller pulled up one of the Aggi’s two massive anchors and donated it to the Santa Barbara Historical Society, where it remains today. The move stirred some controversy. A letter writer to Pacific Underwater News called Miller an “incurable wreck picker” and asked, “Does Captain Miller really believe that the landlubbers visiting the Santa Barbara Historical Society will appreciate the big anchor as much as skin divers did visiting it in 40 feet of water?”

3. Kate and Anna

The Kate and Anna had been out hunting seal and otter when, on April 9, 1902, she made for the shelter of Cuyler’s Harbor on San Miguel Island during a particularly nasty northwester storm. There, her anchor chain broke, and she was quickly beached. “Knowing that there was little hope of saving her, [Captain C. C. Lutjens] and his men went ashore and were given shelter at the island home of Captain W. G. Waters,” reads a Santa Barbara Morning Press article at the time. “The men had left the schooner in a hurry, taking nothing with them. Most of them were wet through when they reached the house and made a sorry sight. They were given every comfort possible.”

The Kate and Anna had been well-known in Santa Barbara waters even before her last voyage. A year earlier, she made headlines in town when one of her crew tried to murder the ship’s cook. And for several years before that, she was suspected of smuggling opium and Chinese immigrants from British Columbia, though the allegations were never proven

4. Winfield Scott

The gold rush brought throngs of fortune seekers to California, many of them by sailing ships and steamers from New York to Panama and into San Francisco. On December 1, 1853, the Winfield Scott — named after a Civil War general and loaded with more than $1 million in freshly mined gold bullion (worth more than $33 million in today’s dollars) — departed San Francisco on her way back east. To save time, her captain, Simon F. Blunt, decided to pass through the Santa Barbara Channel, but he miscalculated at night in a gathering fog and turned southeast for open ocean too soon, crashing full speed into a large rock off Anacapa Island.

More than 500 passengers and crew scrambled onto the pebbly beach of Frenchy’s Cove, where they set up camp and waited nearly a week for rescue. One woman later described the desperate scene in an 1854 letter to New York’s Sun newspaper: “What occurred during the six days’ sojourn on the island was outrageous in the extreme.… Trunks came broken open, carpet-bags cut and their contents extracted; clothing lost and strewn about — money ‘cared for,’ such a general robbery was never before perpetrated.… A Vigilance Committee was appointed, although the gold that was stolen was, under the circumstances, of no account, as the thieves could not buy anything to keep body and soul together; and a person having anything would have been murdered for it.”

An untold amount of gold went down with the Winfield Scott, which is protected by strict antiquity laws that prohibit removing any artifacts, but a 1967 article in Skin Diver Magazine ignited a modern-day rush over the wreck. “Would you believe,” the article read, “a gold strike, near a small island off Santa Barbara? Neither did we, until that warm California autumn revealed the unmistakable glint of gold nuggets in the dredge’s rifle box.” Looting became an issue, and offenders were prosecuted with fines and sometimes jail time. Today, while Park Service officials actually encourage sport divers to visit the site, they keep close watch and sternly warn: Look, but don’t touch.

A passing ship eventually spotted smoke from the camp’s fires and rescued most of the marooned group. It returned two days later for the remaining few. “They were rescued just in time to prevent worse suffering,” according to the woman’s account, “as they had got down from a scanty allowance of breads to a potato a day, and the water had become salt.”

During this frightening experience, many passengers found Captain Blunt’s behavior admirable, even heroic. A letter was presented at the formal investigation into the crash that 200 passengers had signed in support of Captain Blunt’s actions. According to a report in the San Diego Union, the letter read: “In the gentlemanly deportment and kind attention to his passengers, Captain Blunt is without superior indeed. [He] is of so high character as to render it superfluous to mention his sharing his last blanket with his passengers after reaching the rock, and giving his own life preserver to a passenger before leaving the ship.”

Salvage operations were able to recover machinery, furniture, mail, and other items from the Winfield Scott. Soon after, Horatio Gates Trussell of Santa Barbara used some of its timbers and brass in the construction of his adobe home on Montecito Street, today known as the Trussell-Winchester Adobe, and a decorative carved eagle was reportedly found among the wreckage and installed at the Lobero Theatre.

5. George E. Billings

The remains of the largest and last sailing vessel built by the revered Hall Brothers was discovered only recently, in 2011, more than 70 years after she was scuttled off Santa Barbara Island. The George E. Billings, built in 1903, first hauled lumber before she was converted into a sports-fishing barge. Then, strict regulations passed in the 1940s to eliminate offshore gambling made it impossible for many older vessels like the Billings to meet compliance. She was “towed to a lonely island reef and burned,” a news account states. Archeologists and historians had been actively searching for the wreck since the ’90s.

6. Jane L. Stanford

Jane Elizabeth Lathrop Stanford, this four-masted barkentine was built in 1892 for transpacific lumber routes between Hawai‘i, Australia, and China. After WWI, she was converted to a fishing barge, where the daughter of one of her captains spent seven years of childhood. In a 1992 interview, she recalled using dried shark’s eyes as marbles and stringing together necklaces of fish vertebrae.

On August 31, 1929, the Jane L. Stanford was accidentally rammed by another boat that left an eightfoot hole in her hull. Deemed too costly to fix, she was towed from Santa Barbara to the east end of Santa Rosa Island, where she was demolished with dynamite by the U.S. Coast Guard. A Los Angeles Times story described the action: “The explosions, plainly heard in this city during the morning, caused some alarm among housewives who kept police busy answering telephone calls…. The terrific force of the blasts hurled parts of the barge over a space of more than two miles, scattering pieces of wood and metal along the beach. The huge boiler was blown more than twenty feet into the air in one blast.”

7. Chickasaw

This hulking American freighter began life in 1942 as a U.S. Navy transport, operating in both Europe and the Pacific theaters, before she was demilitarized in 1946 and sold to the Waterman Steamship Company out of Alabama. On February 7, 1962, the Chickasaw was bound for Wilmington, California, from Yokohama, Japan, when she ran aground in thick fog on the south side of Santa Rosa Island. Her cargo included plywood, dishes, toys, and optical supplies. The Coast Guard rescued 46 crew plus four elderly tourists, and a salvage team removed the cargo, along with brass, copper, wiring, electric motors, and turban pieces.

Later that year, in May, Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s deputies arrested a Ventura scrap dealer for stealing remaining electronics and navigational gear from the Chickasaw. He admitted towing away one of the freighter’s lifeboats stocked full of “souvenirs,” but he claimed the boat sank in the Channel on his way back to town.

8. Grey Ghost

During Prohibition, rumrunners played cat and mouse with the Coast Guard among the islands, where small caves and remote coves offered convenient hiding places. On November 13, 1926, a Coast Guard patrol spotted the Grey Ghost darting along the south edge of Santa Cruz Island and fired three shots across her bow. The Grey Ghost “failed to heave-to,” the official incident report reads, and “it was then apparent to the officer-in-charge … that she was loaded with contraband and endeavoring to escape.”

The Coast Guard gave chase and fired 59 shots from its autocannon, scoring six direct hits, including one through her pilothouse and another at her starboard waterline, “doing considerable damage.” Meanwhile, the machine-gunner burned through 10 magazines of ammunition, “making numerous hits.”

Now close to sinking, the Grey Ghost turned toward the coast and ran ashore. Its single occupant jumped out and escaped. It took three search parties, but the Coast Guard finally found the man hiding among some boulders. They seized 200 sacks of imported whiskey and two oak halfbarrels of liquor (about 20 gallons each) from the wreck.

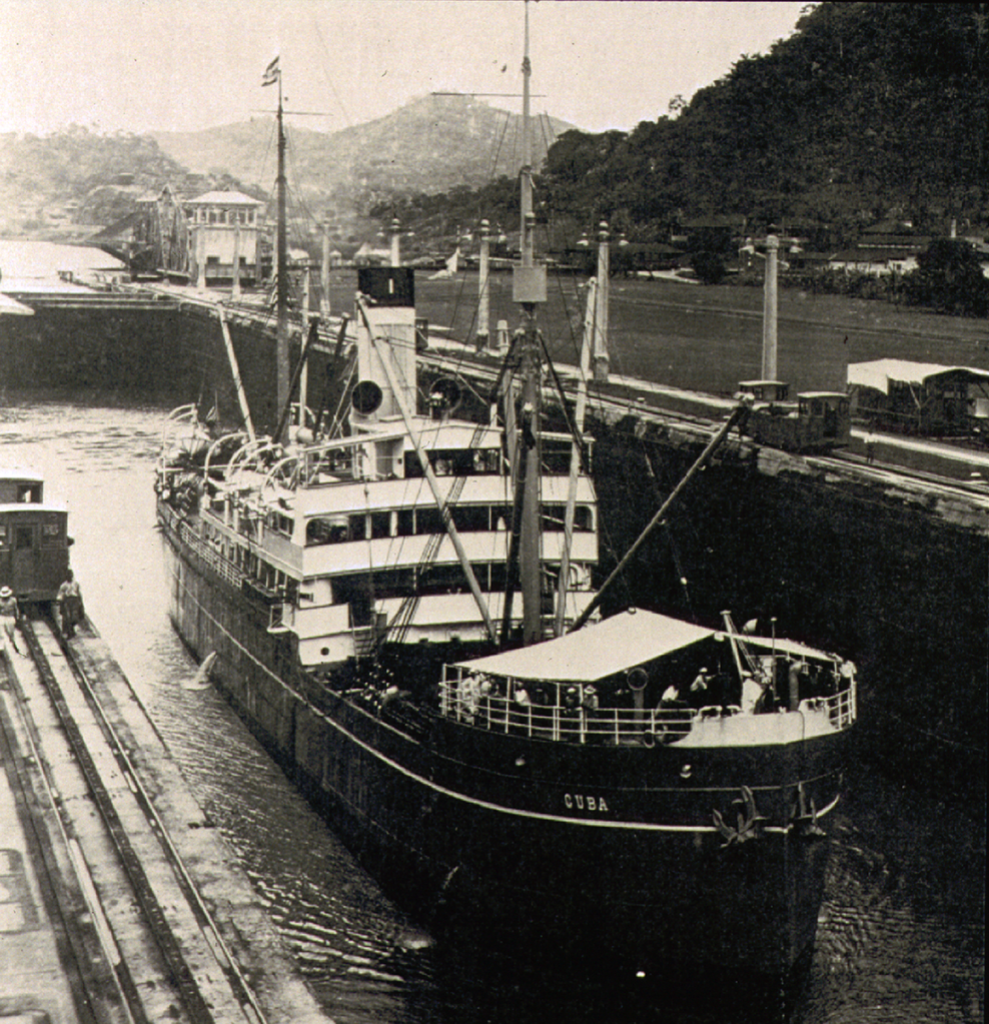

9. Cuba

Stuck with a broken radio and no fix on land, Captain Charles J. Holland was forced to creep the Cuba through the Santa Barbara Channel for three days by dead reckoning, a tricky method of navigating by course, speed, and elapsed time alone. His luck ran out when the Cuba struck a reef a quarter mile off San Miguel Island. It was 4 a.m. on September 8, 1923.

Because the steamliner’s hull contained bars of silver bullion, along with mahogany and coffee, Holland and eight armed crewmen remained on board while the rest of the ship’s 115 passengers scrambled into lifeboats. Two of the boats “put upon the beach at Point Bennett after dealing with some aggressive sea lions,” a contemporary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) report says. Distress calls went out, and all passengers and crew were rescued.

Strikingly, within hours of the incident and just a few dozen miles away along the mainland coast, seven U.S. Navy destroyers steaming south at 20 knots slammed into an outcropping of rocks called Devil’s Jaw, killing 23 sailors. Known as the Honda Point Disaster, the same NOAA report said there was speculation at the time that the additional radio traffic during the Cuba rescue may have played a role in the lead destroyer making its navigation error.

Ira Eaton, who was running a resort on Santa Cruz Island in those days, salvaged many of the Cuba’s furnishings, including tables, linens, and silverware. He also found 500 letters aboard that he returned to postal authorities.

10. Spirit of America

Built in 1943, the wood-hulled Spirit of America was originally operated as a minesweeper out of Los Angeles. After a fire on board caused major damage, her salvage rights were purchased in the 1960s by Al Kidman, a husky ex-logger from Idaho who was known as the “Flag Officer of the Ghost Flotilla” because he bought derelict vessels and sold the recovered parts.

Kidman often ran afoul of the law. After he got in Dutch with the Coast Guard for illegally docking his recovered ships in the Los Angeles Harbor, he started storing them on the bottom of the harbor instead. He’d sink the boats, and when he wanted a part, he’d simply dive down for it. “His file with the Los Angeles Harbor Master’s office regarding his misdeeds is three-inches thick,” says a Los Angeles Times article.

But Kidman didn’t sink all his ships. The Spirit of America was allegedly operated as a floating bordello in San Pedro and Long Beach, and when Kidman finally towed her out to Santa Cruz Island in 1980 for salvage, she broke loose of her mooring and crashed in Scorpion’s Harbor, scattering shreds of red carpeting, mattresses, and mirrors along the shoreline. Operators of the nearby Scorpion Ranch reportedly recovered a bathtub and installed it at the property

11. J.M Colman

The J.M. Colman sank in heavy seas just inside Point Bennett on September 4, 1905. As the water rushed over her deck, her first mate drowned trying to drag a chest of gold from the hold. At least, that’s how one story goes. Another says he was snatched by a “devilfish,” or giant squid.

While the man’s true fate remains unknown, what is known is that the Colman carried enough salvageable lumber to build a 120-foot-long ranch house on San Miguel and a cabin on Santa Cruz. She also carried loads of flour in twill bags, which, when wetted, sealed their contents and kept them dry. The flour was used on the islands for years after.

The two men in charge of recovering the Colman’s cargo were described by the Santa Barbara Morning Press this way: “That enterprising mariner, Captain McGuire, and Captain Vasquez, one of the most experienced salts on the coast.”

Correction: While a typical sea voyage from New York to San Francisco during the gold rush would have taken travelers to Panama, it would not have taken them through the Panama Canal, which did not open until 1914.

You must be logged in to post a comment.