High School Drama at

Santa Barbara, Dos Pueblos,

and San Marcos

Historical Shift on Stage,

with Three Women at the Helm

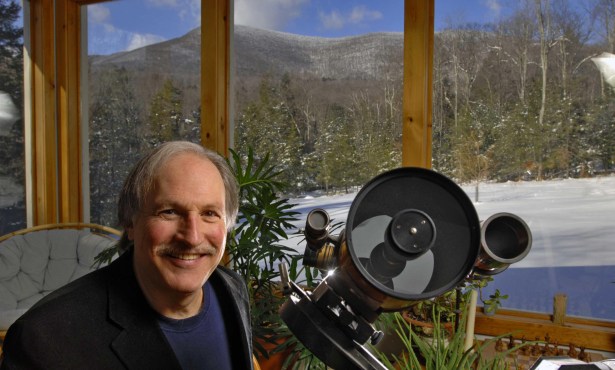

By Callie Fausey | Photos by Ingrid Bostrom

September 7, 2023

Prologue

Three high schools, all alike in dignity, in fair Santa Barbara, where we lay our scene, from ancient theatrics break to new teachers, where creative women direct creative teens.

For the first time in the Santa Barbara Unified School District’s history, going back a century, all three high schools — Santa Barbara, San Marcos, and Dos Pueblos — have an entire cast of female theater directors.

Quoting Shakespeare may be overdramatic, but it seemed fitting. High school, notoriously, is full of drama and clichés.

At the risk of sounding like a teenager’s inner monologue in a coming-of-age movie, graduating from junior high’s relative innocence and stumbling into the intersection of self-consciousness and self-realization in a rabble of uncertainty and angst would drive anyone to melodramatics.

But, otherwise, I loved my time at Santa Barbara High School.

At least, I loved the theater. I was never on stage — save for one theater class and a failed audition — but I did stage tech and enjoyed exploring the space (including sneaking into the rafters, where things like “sex” followed by a smiley face were crudely spray-painted on air vents).

It was a welcome escape from the trials and tribulations of teenagedom.

But I digress.

The lead roles in Santa Barbara Unified’s high school drama program are played by Shannon Saleh at San Marcos, Emily Libera at Dos Pueblos, and Gioia Marchese at Santa Barbara.

They gave me a “behind-the-scenes” look at what it’s like to teach and inspire Santa Barbara’s teenagers to express creativity with confidence — as well as what productions to expect this year.

“There are just three of us, and our job is super unique,” Saleh explained. “We need each other.”

Act I: Lifelong Theater Kids

About five minutes into our interview, a couple of boys shuffled into Saleh’s office at San Marcos. She told them she couldn’t chat at the moment, but not without adding, “I’m so happy to see you!”

She left her door open, she explained, because she missed her students. Open-door policies are common in the realm of high school drama, where students treat the theater as a sanctuary.

“We barely have alone time throughout the day — maybe unless we’re using the restroom,” laughed Libera.

In theater, there is no built-in feel of classroom hierarchy. Although many teachers go above and beyond for their students, theater teachers see more opportunities for bonding.

“We don’t have to put them in rows and desks,” Saleh explained. “We don’t have the same kind of check-the-box standards that a lot of core subjects have to have; we get to be creative.”

“Theater is about risk, and taking personal risks to make something beautiful,” Libera added. “That’s also a thing that you don’t have to do in other classes. You don’t have to risk to do math.”

But it’s also incredibly rewarding, Marchese explained.

“I just love watching these humans right at the point where they’re going to launch out on their own,” she said.

However, with those rewards comes a chaotic schedule. Their teaching lives are, in more ways than one, dramatic. Saleh started auditions for her fall play on the second day of school. Libera and Marchese are on a similar timeline.

They work odd hours, late nights, on weekends, and sometimes early in the morning.

“Life balance — I haven’t figured that piece out yet,” Libera said.

But she will have time: “People live and die in these programs.” At that, Saleh called her dramatic. But Saleh herself is a prime example.

All three directors were “tried-and-true” theater kids. Say what you will about theater kids, but they are undoubtedly dedicated to the craft.

Although they all grew up on stage, Saleh is the veteran director. For our interview, she wore her confident credo “I Am Kenough” T-shirt (from the Barbie movie), after checking its coolness with her male students. “And they were like, ‘Absolutely,’ ” she said.

She’s starting her sixth year at San Marcos, but she got her start in town in 1997 with a position at La Colina Junior High. She’s acted in town for years, fostering a passion for performing arts that she never grew out of. In high school, she spent every summer teaching children’s theater.

Once you’re in, it’s hard to get out, Saleh said, adding, “You get a little bit addicted.” She highlighted that Libera is a “fricking amazing” singer and performer, and they both enjoy being able to use their talents to teach kids.

Libera, hailing from Santa Barbara, nurtured her theater passion in her hometown. Her lifelong devotion to performing led her through La Colina, where Saleh was actually her theater director.

“Neither of us has aged at all,” Libera joked. “We’re just looking young and gorgeous forever.”

It’s just one example of full-circle investment in theater — students who join usually stay involved until graduation, and, oftentimes, come back to work or volunteer as alums.

For Libera, her theater directors helped her find her voice and her confidence, and she now wants to pass that on to the next generation.

“I knew Emily when she was little, and now she’s like this so competent, capable, fabulous, kicking-butt woman,” Saleh chimed.

Going to San Marcos after junior high, Libera thrived under the guidance of David Holmes, who retired in 2014 after his farewell production of the camp classic The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Local operas and productions earmarked Libera’s on-stage upbringing, leading to a master’s from UCSB and an early directing career at La Cumbre Junior High. Both she and Saleh transitioned from teaching English to theater, “which plays perfectly into theater stuff, making written material come alive. It’s just a natural segue,” Libera explained.

With Clark Sayre’s retirement, Libera eagerly embraced the chance to helm Dos Pueblos’ esteemed theater program, realizing her directing aspirations.

Last year was her inaugural year at Dos Pueblos, which she hailed as an incredible journey. Her first

production at the school was The Plot, Like Gravy, Thickens, a mystery by Billy St. John.

“The kids are amazing and welcoming,” Libera said. “And they don’t give me any issues with the fact that I went to San Marcos.”

Like Libera, Marchese is also a product of Santa Barbara, now following in the footsteps of longtime director Otto Layman at Santa Barbara High.

Her journey began at Montecito School of Ballet. In 4th grade, she was taken under the wing of the then-soon-to-be Dos Pueblos High School (DPHS) theater director Sayre, who cast her in her first youth theater show and helped her discover her love for theater.

Later, she attended Santa Barbara High School (SBHS), but left to briefly chase an acting career in New York City, eventually shifting to focus on choreography and directing, producing independent films and directing plays in local theaters in New York and L.A. (she even has an IMDb page).

When she reached her mid-thirties, she was ready for a transition. Her decision to move home was serendipitous, catalyzed by a call from Sayre, a longtime friend and mentor.

“He called me out of the blue and asked if I might have time to work on a show he was doing at Dos Pueblos,” Marchese explained.

She was in between gigs at the time, so she decided, why not? She didn’t expect to find her calling, but she never left.

For 12 years, Marchese worked alongside Sayre and choreographed for him on shows such as Tarzan, Mary Poppins, and Newsies.

Sayre recommended Marchese get her teaching credential so she could fill his shoes after he retired. But right as his job opened up, Libera applied for an interdistrict transfer and got the spot.

At first, Marchese was disheartened. Then Justin Baldridge, who ran the SBHS program from 2020 to 2022 after Layman, left for a job in Los Angeles, and Marchese began her first year at SBHS with her own program. “I feel like everything worked out the way it was supposed to,” she said.

Santa Barbara High’s theater program is going through a kind of “renaissance,” Marchese noted, as she establishes a new presence and program for the school, in the wake of Layman’s 25-year tenure.

My own memory of Layman’s theater class is tied to one instance. At the tender age of 15, after going through a devastating breakup with my boyfriend of maybe two weeks, Layman paired us together to act out a scene as our final project. The script was — to my then-horror and now-amusement — about a couple breaking up.

Marchese is also rebuilding the program after the universal COVID-19 rough patch. And she’s not the only one: Libera and Saleh admitted that teaching during the pandemic was “soul-sucking.”

“But it was important to stay connected to kids,” Saleh said, adding that she even managed to pull together an outdoor production of Mamma Mia! But it was hard to teach such a social art form while social distancing.

Marchese is still finding her footing, but she is eagerly providing her students with the opportunity to flex their creative muscles and “excavate the depths of their humanity,” in the words of the school’s theater webpage.

Her productions last year were The Crucible and Rocky Horror.

“The freshman class is, all of a sudden, twice as big as last year in terms of signups,” she said. “So I feel like it’s definitely coming back.”

Even though each of the trio all has their own preferred flavor of theater and modus operandi, they are the same “in the heart of it all,” Libera explained. “It just feels like we all love what we do.”

A noticeable shift in operations between the past and present eras was the loss of competitive edge. Saleh certainly felt that tension melt away with Marchese and Libera’s arrivals: They’re a tight-knit group who can relate to each other’s joys and struggles and reach out if they ever need support. “Which is very different from when I started,” Saleh said. “When it was me and the two boys.”

“There was a little bit of prickliness,” she added. “We’re not having it — they’re doing an awesome job teaching. I want to take my kids to see their stuff.”

With women heading all three high school theater departments for the first time, Marchese said it’ll be interesting to see how they all grow, “but it’s pretty monumental and exciting for our community.”

Act II: Supporting Roles

As it turns out, it’s incredibly expensive to put together a high school theater production. It costs roughly $35,000 per show, and they don’t even pay the actors. The directors are thrilled if they’re able to just break even on ticket sales, which, alongside advertising, only cover a fraction of the actual production costs.

They end up dedicating their own time to fundraising and budgeting, with a couple of small stipends from the district every year to hire other necessary tech, costume, and musical staff. But they’re expected to stretch thin to cover two main shows.

Raising money to cover production costs and supplement staff stipends is, as Marchese put it, a full-time job in and of itself.

“To be honest, the school district does not value arts except in their wording,” Saleh said.

The others echoed that sentiment. However, they emphasized that the current administrations at their individual sites have been nothing but supportive (although Santa Barbara High is in flux, following principal Elise Simmons’s resignation in August).

“My principal, Bill Woodard, is a big fan,” Libera said. “He’s understanding of the chaos that is running a theater department and is ready to give me what I need to make it work.”

Libera said she would like to see the school district’s vocal support translated onto paper in the form of funding for the whole program, everything from power drills to paychecks.

The turnover for support staff is high because the pay is not livable, she explained, and the work is strenuous, making it hard for their programs to grow. “We struggle to keep these really talented tech directors that students look up to,” Libera said.

“We are one person, and it’s a lot to do already, without a staff, and then even with the little staff we’re able to hire out of our own fundraising.”

Getting people to stick around crosses into the conversation around housing in Santa Barbara — Marchese can’t even afford to live in the neighborhood where she teaches.

“You know, there’s always the expectation in the arts that it’s so fun, that’s kind of your reward,” she said. “If you don’t want to do the extra work, somebody else will always want that position.

“But I think all three of us really love what we do, and are really committed to what we do. But people are starting to recognize that they want to be compensated fairly for the hours that they’re putting in…. I think Shannon and Emily and I are all trained to work together to improve those things, where we can, little by little.”

It’s difficult to compare it to the district’s sports programs, where games sell out stadiums, buttressed by a national culture of built-in support for athletics. But while the district recently shelled out nearly $30 million to finish the (granted, long-overdue) renovations on Santa Barbara High School’s 93-year-old stadium, many of the school’s performing arts spaces remain in a sorry state.

Marchese said that former SBHS principal Simmons had indicated plans for a campaign to fix up the theater. But now that she’s gone, Marchese doesn’t know where those plans stand.

“We just don’t have space to house all the programs we have, and our theater is very old and pretty worn-down,” Marchese said.

Santa Barbara Unified Superintendent Hilda Maldonado explained that the district is working on a new strategic arts plan to support theater, dance, music, and visual arts. They had to put it on hold last year, but she hopes to bring it to the school board in the coming months.

“As far as the theater program, the teachers do an incredible job. We could never support them enough, but, that said, I think that there’s a lot more that we need to be doing for theater,” Maldonado said. “Improving our performing arts facilities, particularly. But I’m really proud of what our teachers do, and I have gone to some of the plays in past years. I’m hoping to go to more of them.”

What the district lacks in support, the students and their community work hard to make up for.

Students eagerly take on responsibilities such as designing and maintaining the theater’s web pages and social media accounts, building sets, and selling ads for the programs.

It takes some of the weight off the directors’ overburdened shoulders and provides students with opportunities to learn what it means to produce a show, which they can then pass down to the next cohort.

“We lean a lot on parent support,” Libera added.

When Saleh didn’t have a tech guy to help her teach her stagecraft class last year, she had a carpenter come in to coach students for the first two weeks. Libera chimed in to ask how she had hired him.

“He was just a dad who happened to be a finish carpenter,” Saleh replied.

“I have a dad like that,” Libera said.

She added, “We love to utilize the community gallery and involve parents, people who are passionate about education and the arts. Parents were really helpful this last year, and hopefully more this year.”

“Everybody cares so much about theater and kids that they pour in, and that helps us to maintain,” Saleh said.

Parent volunteers founded the Santa Barbara High School Theater Foundation in 2005 to support theater arts. They help with the high costs of purchasing production rights for shows, replacing equipment, and repairing the theater — such as replacing the lower-level seats and upgrading the lighting system.

Other nonprofits, such as the Foundation for Santa Barbara High School and the Santa Barbara Bowl Foundation, have also donated to the survival of the arts in Santa Barbara Unified. Parents help, but if the directors want to produce shows on a scale they desire for their students, that often requires hiring professionals and, of course, a lot of fundraising.

“God bless Santa Barbara Bowl Foundation,” Saleh expressed, speaking for all three of them. “They accept grant requests from us for both semesters, and that may only fund the piano player, but it’s still so helpful to have any assistance at all.”

As Marchese sees it, she’s slowly gathering support for her program. “And I think over time, as I get to know the families and the community, that will just grow,” she said.

Act III: Showtime

Each department is on a tight schedule to keep its fall production on track, as each one takes nine to 10 weeks to put together.

“And that’s by the skin of your teeth,” Saleh explained. “I need all of the minutes to do it.”

That means everything from the set building to the staging to the acting. Saleh is putting on The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time at San Marcos this fall, which will be her first drama. She explained that it’s a beautifully written play about the brain of a boy with autism, and how people in the world respond to him and how he responds to his world.

“My boys last year were begging me to do a drama,” she said. “But this has comedy in it. It’s a really unique, special play that requires a particular kind of compassion. I’m very excited to start that.”

Libera’s focus for the beginning of the school year is Almost, Maine, a play about the mystical powers of the human heart and the aurora borealis, which goes up in November. After the fall play, they move into their “holiday package” — including student-written, -acted, and -directed SNL-style skits that will run in December, coinciding with auditions for the much-anticipated spring musical.

Her spring musical will be announced soon, she said. In January, though, they’ll do another student-directed production in their advanced theater showcase.

“My student directors learn a lot in the showcase when it comes to putting together a production,” Libera said. “It’s really fun to watch.”

Marchese is going more gothic, with a fall production of Dracula falling right around Halloween. They’ll also have a student-directed show in the New Year to bridge the two seasonal productions.

After Saleh’s fall production, she’ll have 10 directors from the community come and recruit a set of student actors to work with for six weeks, a program she calls “One-Acts.” She said the directors love working with high school students, whom they see as springs of unlimited potential or unmolded clay. “The students are so eager to learn and these directors are so eager to teach that it creates a magical combination.”

Last year, San Marcos began a senior musical production, which this year will be either Charlie Brown or Company; they’re still deciding.

Then, they all jump into spring musicals, the audition process for which will be in December to go up in May. “That’s like the big bang show of the year for all three high schools,” Saleh said. “And I don’t want to announce my musical yet. So, sorry, you can’t have a title.”

At the end of the year, after all the chaos of auditions, memorizing monologues, and singing and dancing, they get to celebrate their hard work with theater awards and parties.

As Libera put it, “We get to relax for a little bit before we do it all over again.”

Take a Bow

When asked how she feels about an entirely women-led theater program, Superintendent Maldonado said she’s proud and “excited to support them.” As a 58-year-old woman, she shared that she was presented with a narrow scope of career options as a young girl.

“It’s interesting because education has historically always been female-dominated, but the leaders in education haven’t always been females,” she said.

“I think it’s important that we show young women all the possibilities in the world for their careers. When I was graduating from 6th grade, we were supposed to say our name and what we wanted to be when we grew up. I remember looking at my teachers and asking, ‘What should I say?’ And they said, ‘Just say you’ll be a secretary.’ Not that there’s anything wrong with secretaries, but underneath it felt very narrow, very confined to helping roles rather than leadership roles.”

But breaking the theater’s glass ceiling takes support from the community, and the directors could always use another set of hands to throw stones, so to speak.

You must be logged in to post a comment.